Bail-in measures are designed to inject capital into a bank that gets into trouble. The bank is authorised by the corporate regulator – APRA to take money out of the bank accounts of depositors and to use that money to pay their own bills. The depositor loses their money but does get shares in the bank, which will be worthless, but may come good years down the track if the bank doesn’t go broke.

APRA maintain that the emergency banking measures passed in 2018 by the Turnbull Government did not include a bail-in power. Further, if they used the general powers in that act to order a bail-in, that bail-in would be declared “invalid”.

This is because the Banking Act protects deposits. One Nation’s legal advice is that the emergency powers over-rule the general protections in the Banking Act and APRA do have bail-in powers. One Nation have proposed a bill to clear this up by adding one simple paragraph to the Banking Act that says APRA do not have the powers to order a bail-in.

APRA doesn’t want our bill passed because they know they do have bail-in powers and don’t want us to take them away. This round of questions did extract an admission that APRA does have bail-in powers, but not for deposits. So at least we are getting a little more honesty out of APRA on this matter. We also spoke about their emergency bank rescue plans.

One Nation feels these plans will show a bail-in is part of the plan. Getting our hands on those plans won’t be easy.

Transcript

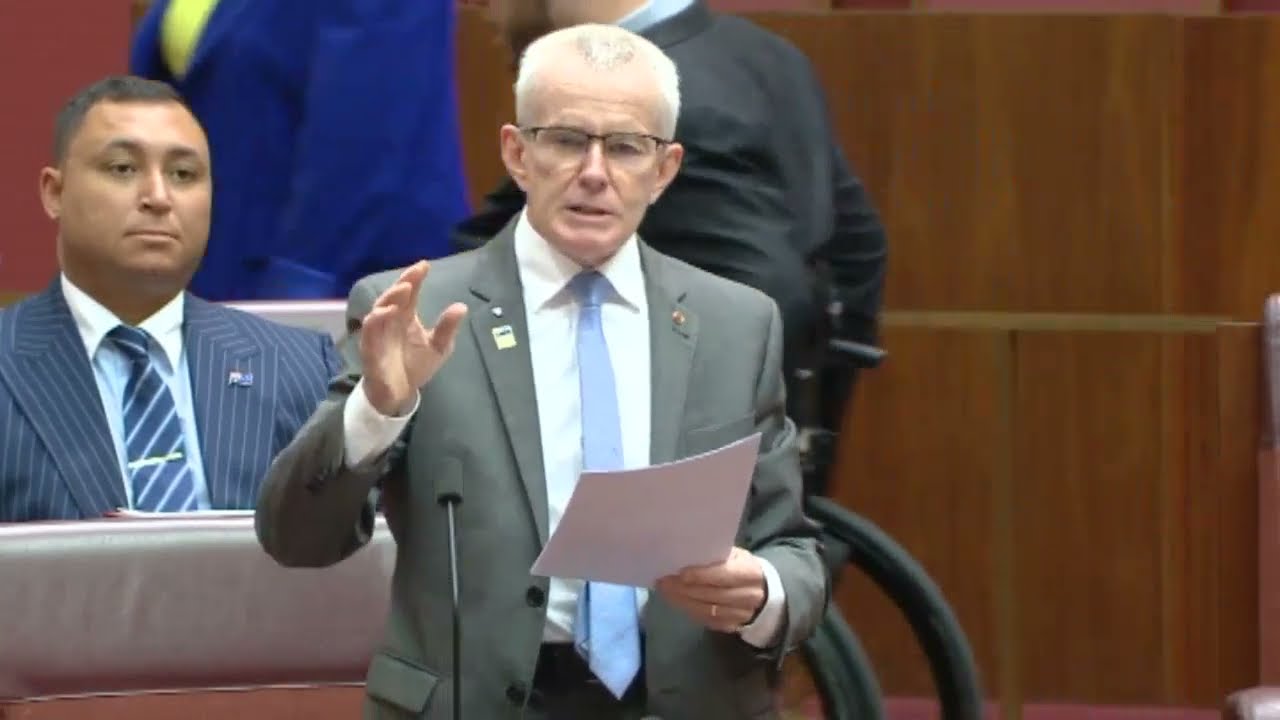

Senator ROBERTS: Thank you all for participating tonight. APRA’s submission 197 to the inquiry into our bank anti bail-in bill—and I am slightly paraphrasing—says that APRA does not have the power to direct Australian authorised deposit-taking institutions to bail in a deposit because that would be inconsistent with the objects of the Banking Act, particularly the paramount objective of protecting depositors, and that such a direction would be found to be invalid. Who would find it invalid?

Mr Byres: It could be challenged by anyone who wished to take it before the courts—that would be the answer. Our direction could be appealed to a court.

Senator ROBERTS: That is my understanding, too—that only a court can find an APRA direction invalid. Can I confirm that it is your position that if a bail-in occurs those depositors who have lost some or all of their money must then take their banks to court at their own expense, with millions of dollars in legal expenses, to seek an order declaring the bail-in invalid? They will have very little in the way of funds to fund that because their deposits have been cleaned out.

Mr Byres: Your question is premised on the assumption that there is a bail-in. I think in our correspondence with the committee and in our submission to the committee on this bill we made very clear that our whole purpose is to protect depositors, not to bail them in. A bail in of depositors would be anathema to the way we operate and our statutory purpose. So I think it is a scenario that is entirely hypothetical, because that would not be a direction that we would give.

Senator ROBERTS: The Financial Sector Legislation Amendment (Crisis Resolution Powers and Other Measures) Act 2018 says APRA has a right to enact emergency powers and they are often said to be overruling. Does that emergency directions power have primacy over the general banking directions in section 2A in the Banking Act?

Mr Byres: I’m not sure where exactly you are referring to, but you are right: we have strong powers to deal with an emergency situation where a bank or another financial institution is in severe financial stress. The purpose of that in the case of a bank, to be clear, is to protect the community and depositors.

Senator ROBERTS: The IMF disagrees with APRA on the strength of the section 2A protections. The IMF has stated that:

The new ‘catch-all’ directions powers in the 2018 Financial Sector Legislation Amendment (Crisis Resolution Powers and Other Measures) Bill provide APRA with the flexibility to make directions to the ADIs that are not contemplated by the other kinds of general directions listed in the Banking Act.

If the IMF are correct, you do have bail-in powers. Is the IMF wrong?

Mr Byres: The bail-in powers that we have relate to capital instruments. Again as we put in our submission to this committee when it conducted its inquiry into that bill, the objective is very clearly to have bail-in for subordinate capital instruments. That act and, in particular, the sections of that act which attracted a lot of attention were designed to make sure that there was legal certainty and that the contractual arrangements that are in those subordinated debt and hybrid instruments would work in this.

Senator ROBERTS: Our bill simply clarifies that you do not have bail-in powers, which is what you’re telling me here today. Why are you opposing our bill when it does nothing more than clear up what the law is saying that you say it is?

Mr Byres: Sorry, Senator. We do have bail-in powers. They relate to certain specific instruments. As the law currently applies to banks, it applies to their subordinated debt or, in the jargon of the bank supervisor, tier 2 capital, and it applies to hybrid capital instruments or additional tier 1 capital. So we do have bail-in power. It was designed to give legal certainty to the bail-in of those instruments if needed. It does not apply to deposits.

Senator ROBERTS: Our bill simply clarifies that it doesn’t apply to deposits, so why would you oppose it? It doesn’t stop the bail-in of other funds, appropriately, but it would stop the bail-in of deposit funds: cheque accounts, savings accounts, small business accounts, private accounts. That’s all it does, so it’s agreeing with you. Why would you oppose it?

Mr Byres: The view we put in the submissions was that it was not necessary because we thought the current law was adequate.

Senator ROBERTS: It doesn’t change anything for you; it complies with what you just stated. I can’t understand why you’d oppose it. It makes two minor changes that are in line with what you’re saying.

Mr Byres: As we said in our submissions, we didn’t think it was necessary.

Senator ROBERTS: Okay. APRA’s 2018 paper titled ‘Increasing the loss-absorbing capacity of authorised deposit-taking institutions to support orderly resolution’ states:

APRA will need to work with ADIs on an ongoing basis to ensure adequate resolution plans are developed and maintained. These plans—

supposedly—

outline how APRA would use its powers to manage the orderly failure of ADIs and identify steps that can be taken to remove barriers to achieving effective resolution outcomes.

Have those plans been drawn up? If so, what are they?

Mr Byres: I’ll start, and then I’ll see if my colleague Mr Lonsdale wants to jump in. One of the things we have to do is prepare for the unexpected. We can never provide a guarantee that a bank—or, for that matter, an insurer or another type of financial institution—won’t get into financial difficulty. We need to have crisis plans, like contingency plans, drawn up for how we would respond in the unlikely—and I stress ‘unlikely’—scenario that a bank was close to failing or was failing. The sorts of plans that we have—we’ve just stepped through what actions we might be able to take and how we would achieve an orderly outcome, but, as I’ve said many times already in my answers to your questions, this is with a view to protecting depositors.

Senator ROBERTS: Just to interrupt there: you said the plans would be drawn up. Have they been drawn up is what I asked?

Mr Byres: We have plans drawn up, yes, but they could always be improved. The institutions themselves are constantly evolving and changing, so the plans always need to be updated to make sure they continue to be current.

Mr Lonsdale: I would just add that this has been a big priority for us this year. In fact, the government has provided APRA with some funding in the budget. A significant portion of it focused on recovery and resolution development, so, as Mr Byres said, there’s a lot of work in continually keeping the plans updated and making sure they’re operationally fit for purpose.